Today, I had a horrible experience in town — and sadly, it’s one that many people with invisible disabilities know all too well.

I parked in a disabled bay. I’m allowed to. I live with multiple sclerosis (MS), a chronic, degenerative illness that affects me every single day, even if you can’t see it.

As I was getting out of my car, a woman approached me and said, “You don’t get to park there.”

I calmly explained that I have MS.

She rolled her eyes. “Oh please, that doesn’t count,” she said.

When I showed her my valid disabled parking disc, she sneered and said, “You can buy those anywhere,” before waving me off like I was some kind of fraud. She didn’t stop there — she berated me in front of strangers, making sure I felt humiliated, belittled, and dismissed. And I think she was filming me, just to twist the knife a little deeper.

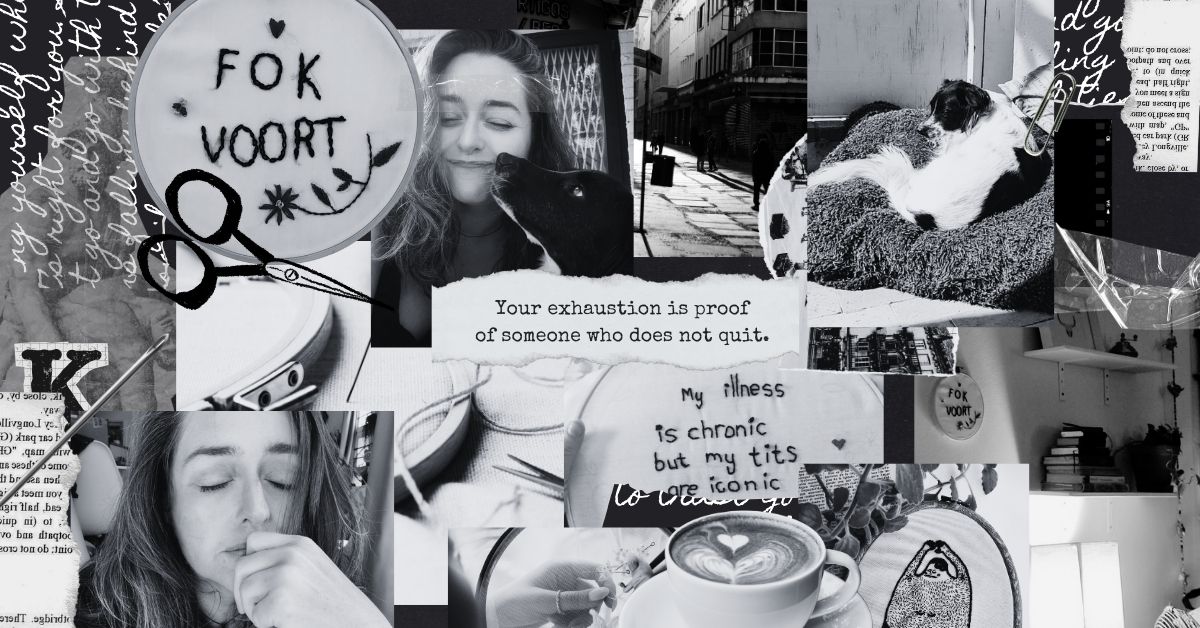

This is what public shaming looks like when you live with an invisible illness. This is the quiet cruelty that people don’t see — or choose not to.

Later that day, I went online to my support group, still shaken, still trying to ground myself. I shared what had happened — and the response was overwhelming. Hundreds of people replied. Not only had they been through similar encounters, but many admitted they now prepare for them. Mentally rehearsing what they’ll say. Keeping their documents close at hand. Some even avoid using accessible bays altogether to sidestep the confrontation.

Think about that for a second: people with real, diagnosed disabilities are bracing themselves to be challenged for using a parking spot designed for them.

Yes, we appreciate when others understand that disabled bays exist for a reason — but now it’s gone further. There’s a new layer of judgment: if your disability isn’t immediately obvious, you’re assumed to be lying. The burden of proof is dumped on the person already struggling.

MS is real. The fatigue, the spasms, the brain fog, the pain — it’s all real. And believe me, if I could trade my disabled badge for a healthy body and a regular parking spot, I would.

But here’s the thing: not all disabilities are visible. And just because someone “looks fine” doesn’t mean they aren’t struggling.

To that woman, and to anyone else who thinks they can play judge and jury in a parking lot: your ignorance isn’t just offensive — it’s dangerous. You’re not protecting the system; you’re making life harder for people already carrying more than you can imagine.

So the next time you see someone in a disabled bay who “doesn’t look disabled,” maybe consider this: your eyes aren’t qualified to diagnose anyone. And a little kindness costs you nothing.

Editor’s Note

I hesitated to share this — but the truth is, silence doesn’t protect us. Sharing these moments matters, because every time we speak up, we make it harder for ignorance to win. If you live with an invisible illness, know this: I see you. And if you don’t, I hope this helped you see us more clearly. Everyone deserves the right to move through the world with dignity — no explanations, no justifications.

I also experience pain inside that is not visible. I also have a disability disc. I am now more prepared for a similar situation.